TITLE:

CHIBOK GIRLS NO MORE

LOCATION: NIGERIA

MEDIA: Photographs

YEAR: 2019

LOCATION: NIGERIA

MEDIA: Photographs

YEAR: 2019

READ MORE:

IN 2014, BOKO HARAM

KIDNAPPED 276

SCHOOLGIRLS.

WHERE ARE THEY NOW ?

By NINA STROCHLIC

The 'Chibok girls’ kidnapping sparked international outrage. More than a hundred are still missing. Today the survivors are trying to rebuild their lives.

Six years ago, Boko Haram kidnapped 276 schoolgirls sparked international outrage. More than a hundred are still missing. Today the survivors are trying to rebuild their lives.

For five years a rebel insurgency in northeastern Nigeria had terrorized the region and shut down schools. The Government Secondary School for girls in Chibok had reopened in April 2014 for students to take their final exams. In a region where less than half of all girls attend primary school, these students had defied the odds they were born into long before the war reached them. But around 11 p.m. on April 14, trucks of militants from Boko Haram, whose name roughly translates to “Western education is forbidden,” forced 276 girls from their dorms onto trucks and drove toward the lawless cover of the Sambisa forest, a nature reserve the jihadist group had taken over to wage a bloody war against the government.

The attack sparked #BringBackOurGirls, an international campaign embraced by then U.S. First Lady Michelle Obama. Chibok, a remote, little-known town before the kidnappings, came to represent some of Nigeria’s most crucial issues—corruption, insecurity, the invisibility of the poor. Media covered every development: The 57 girls who escaped early on; the ordeal of 10 of the girls who wound up in multiple American schools; videos released by Boko Haram showing sullen captives; two emotional releases of a total of 103 girls, reportedly in exchange for money and prisoners; four girls who are said to have fled later on their own.

Of the 276 Chibok students kidnapped, 112 are still missing. Some are believed to be dead. Two and a half years ago, the government arranged for more than a hundred survivors to study at a tightly controlled campus in northeastern Nigeria. Since then, there’s been relative silence.

Over the years the students from Chibok have been paraded in front of cameras when it has served a purpose. When they were in Boko Haram captivity, the shocking image of hundreds of girls in gray hijabs was a sign of the once scrappy group’s rise to power. Once they were in government custody, a colorful press conference with the president just a day after their rescue offered the government a political triumph. Now, they are grown women. When will they choose how their story is told?

The Nigerian government and private donors are covering the costs of at least six years of education for each student. Some are eyeing law school. Others plan to become actresses, writers, accountants. Fifteen have graduated from the NFS high school program and are studying at the university.

Mary K., who escaped on the day after the kidnapping, arrived on campus in 2014, unable to speak English. After two years, she was accepted to AUN. The transition wasn’t easy. She knew other students gossiped about her, and thought about transferring to another school. Now she roams campus and seems to know everyone. Once a week she mentors a group of NFS students on how to manage their time, perfect their English, and pass the three standardized tests they need for AUN admission. This year she’s spending a semester abroad, in Rome.

Not all the survivors of Boko Haram’s war have such opportunities. In Borno State, the epicenter of the crisis, classes were canceled for two years. There and in two neighboring states, roughly 500 schools have been destroyed, 800 are closed, and more than 2,000 teachers have been killed.

Many women held prisoner by Boko Haram return to communities that fear them and families that shun them. Gloria doesn’t know when, if ever, she can resume her old life. “There’s nothing left at home to go back to,” she said.

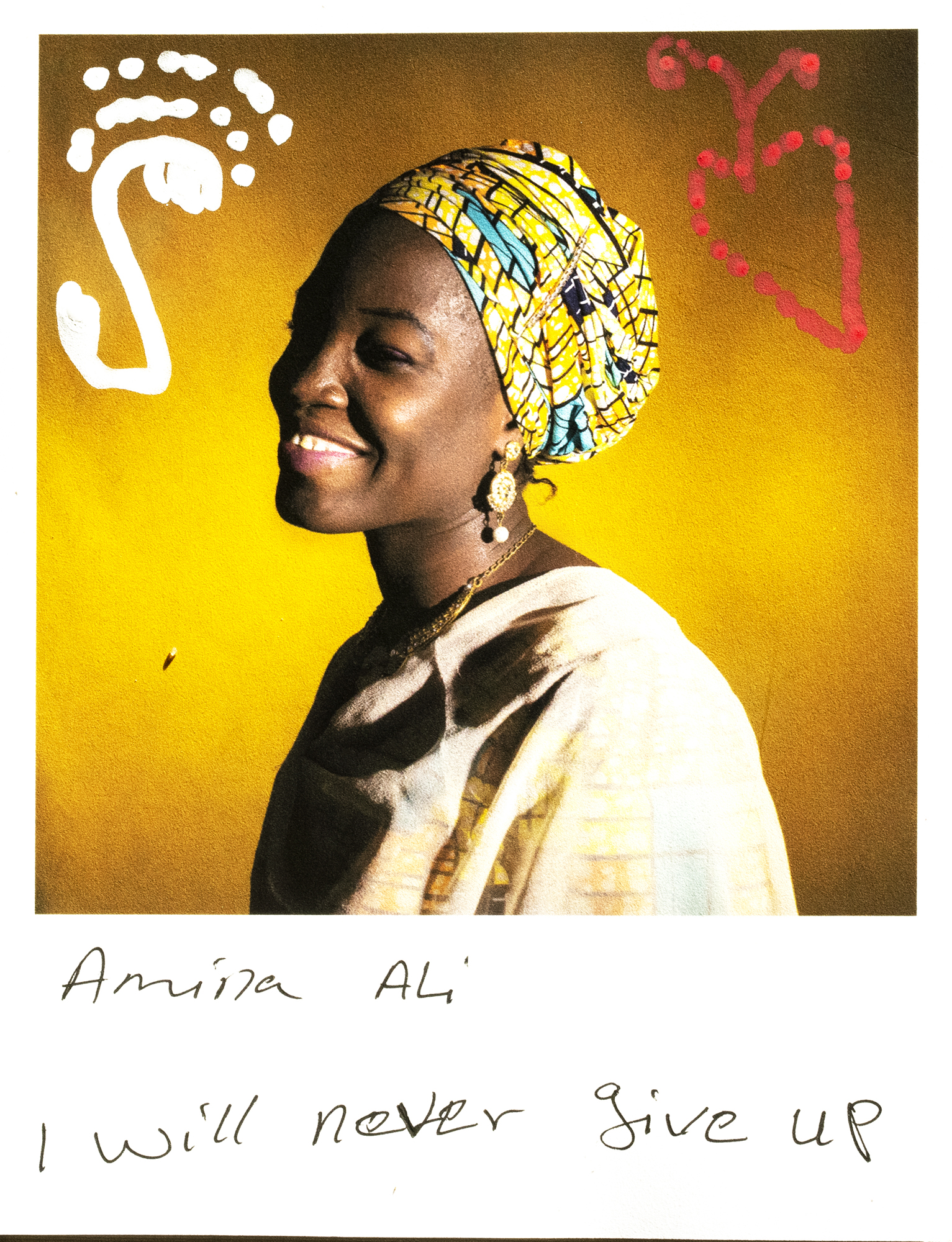

In May 2019, a week before the start of their summer vacation, the Chibok students prepared to mark the anniversary of their release from captivity. “It’s very sad because we remember our sisters in the forest,” said Amina Ali, as she dressed for dinner after a day of rehearsals for the day’s events. “And here we are, happy.”

The next day the drama club performed a play in which two girls were kidnapped for ransom and their families fought to bring them back. The script poked fun at ineffective police, lazy elected officials, and greedy kidnappers. When the captives were freed and reunited with their families, the audience burst into applause. At the end, a row of students read messages for their missing classmates before a balloon release.

A few unique factors propelled the Chibok kidnapping to the national and then international stage: the number of victims, the fact that they were taken from school, and the organized efforts of the community to publish their names and photos. For weeks after the kidnapping, Nigerians with signs and duct-taped mouths swarmed Unity Fountain, a sparse park sandwiched between lanes of speeding cars in central Abuja. The hashtag #BringBackOurGirls became a global cry.

Six years later, a handful of protestors are left. The prevailing attitude in Nigeria, said a businesswoman named Aisha Yesufu, who wore a red hijab with “Bring Back Our Girls Now” printed on the front, is that most of the girls have returned and society should move on.

Every day at 5 p.m. she and a few others gather in the same park for a quick protest. “When will we stop?” Yesufu bellowed. Cars honked, and the sky threatened to release another torrent of rain on a wet spring day.

“Not until they’re back!” the men around her responded. All but one of them were related to a kidnapped student. “The fight for Chibok is the fight for the soul of Nigeria!”

Six years ago, Boko Haram kidnapped 276 schoolgirls sparked international outrage. More than a hundred are still missing. Today the survivors are trying to rebuild their lives.

For five years a rebel insurgency in northeastern Nigeria had terrorized the region and shut down schools. The Government Secondary School for girls in Chibok had reopened in April 2014 for students to take their final exams. In a region where less than half of all girls attend primary school, these students had defied the odds they were born into long before the war reached them. But around 11 p.m. on April 14, trucks of militants from Boko Haram, whose name roughly translates to “Western education is forbidden,” forced 276 girls from their dorms onto trucks and drove toward the lawless cover of the Sambisa forest, a nature reserve the jihadist group had taken over to wage a bloody war against the government.

The attack sparked #BringBackOurGirls, an international campaign embraced by then U.S. First Lady Michelle Obama. Chibok, a remote, little-known town before the kidnappings, came to represent some of Nigeria’s most crucial issues—corruption, insecurity, the invisibility of the poor. Media covered every development: The 57 girls who escaped early on; the ordeal of 10 of the girls who wound up in multiple American schools; videos released by Boko Haram showing sullen captives; two emotional releases of a total of 103 girls, reportedly in exchange for money and prisoners; four girls who are said to have fled later on their own.

Of the 276 Chibok students kidnapped, 112 are still missing. Some are believed to be dead. Two and a half years ago, the government arranged for more than a hundred survivors to study at a tightly controlled campus in northeastern Nigeria. Since then, there’s been relative silence.

Over the years the students from Chibok have been paraded in front of cameras when it has served a purpose. When they were in Boko Haram captivity, the shocking image of hundreds of girls in gray hijabs was a sign of the once scrappy group’s rise to power. Once they were in government custody, a colorful press conference with the president just a day after their rescue offered the government a political triumph. Now, they are grown women. When will they choose how their story is told?

The Nigerian government and private donors are covering the costs of at least six years of education for each student. Some are eyeing law school. Others plan to become actresses, writers, accountants. Fifteen have graduated from the NFS high school program and are studying at the university.

Mary K., who escaped on the day after the kidnapping, arrived on campus in 2014, unable to speak English. After two years, she was accepted to AUN. The transition wasn’t easy. She knew other students gossiped about her, and thought about transferring to another school. Now she roams campus and seems to know everyone. Once a week she mentors a group of NFS students on how to manage their time, perfect their English, and pass the three standardized tests they need for AUN admission. This year she’s spending a semester abroad, in Rome.

Not all the survivors of Boko Haram’s war have such opportunities. In Borno State, the epicenter of the crisis, classes were canceled for two years. There and in two neighboring states, roughly 500 schools have been destroyed, 800 are closed, and more than 2,000 teachers have been killed.

Many women held prisoner by Boko Haram return to communities that fear them and families that shun them. Gloria doesn’t know when, if ever, she can resume her old life. “There’s nothing left at home to go back to,” she said.

In May 2019, a week before the start of their summer vacation, the Chibok students prepared to mark the anniversary of their release from captivity. “It’s very sad because we remember our sisters in the forest,” said Amina Ali, as she dressed for dinner after a day of rehearsals for the day’s events. “And here we are, happy.”

The next day the drama club performed a play in which two girls were kidnapped for ransom and their families fought to bring them back. The script poked fun at ineffective police, lazy elected officials, and greedy kidnappers. When the captives were freed and reunited with their families, the audience burst into applause. At the end, a row of students read messages for their missing classmates before a balloon release.

A few unique factors propelled the Chibok kidnapping to the national and then international stage: the number of victims, the fact that they were taken from school, and the organized efforts of the community to publish their names and photos. For weeks after the kidnapping, Nigerians with signs and duct-taped mouths swarmed Unity Fountain, a sparse park sandwiched between lanes of speeding cars in central Abuja. The hashtag #BringBackOurGirls became a global cry.

Six years later, a handful of protestors are left. The prevailing attitude in Nigeria, said a businesswoman named Aisha Yesufu, who wore a red hijab with “Bring Back Our Girls Now” printed on the front, is that most of the girls have returned and society should move on.

Every day at 5 p.m. she and a few others gather in the same park for a quick protest. “When will we stop?” Yesufu bellowed. Cars honked, and the sky threatened to release another torrent of rain on a wet spring day.

“Not until they’re back!” the men around her responded. All but one of them were related to a kidnapped student. “The fight for Chibok is the fight for the soul of Nigeria!”